Definitely Dreaming

By Halle Catalina Brown

An Ecuador study abroad excursion feels like an 'unimaginable, wild dream'

August 25th, 2021 | SIT Study Abroad

Halle Catalina Brown studied abroad on SIT Ecuador: Comparative Ecology and Conservation in fall 2019 and blogged about her experiences. This article and photos from her blog are reprinted with permission.

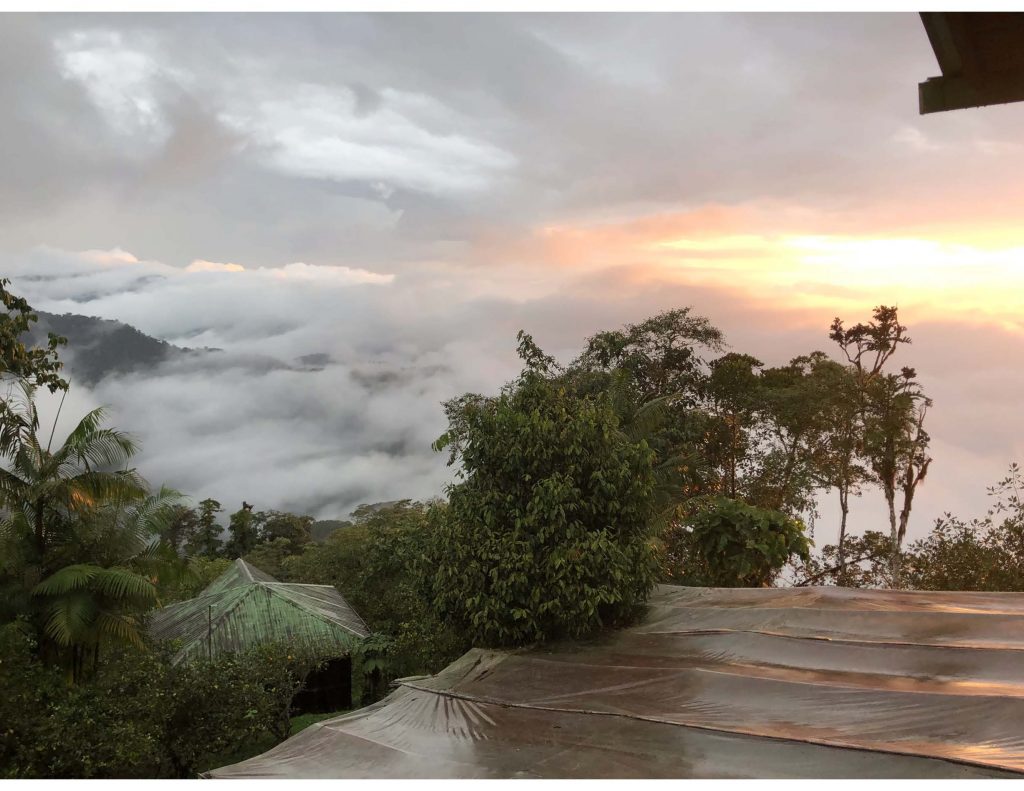

Exploring the cloud forest for five days and our trip to the Amazon was like, 'Someone pinch me, I think I'm dreaming'.

"Ah! Found stinging nettle!" Shannon yelled from deep within the jungle of Marantaceae plants. I stepped off the trail to follow behind her, cringing at her pain yet laughing at the ridiculousness of the situation. We were only two meters off the path, but for all the vegetation that engrossed us, we could have been in the dead center of the Ecuadorian cloud forest. The leaves were the length of half our bodies and each plant grew centimeters from each other, creating a dense forest of vines and moss. Decaying wood and slick mud were underfoot, likely housing a variety of insects and spiders in the silvery webs.

I eventually pushed my way to the area Shannon was standing, carefully avoiding all leaves that looked remotely like stinging nettle. She was bent over a growth of mushrooms like lacy shelves on a dead piece of wood.

Our plan was to survey the area 2 meters on either side of the trail, noting the type of material the mushrooms grew on and at what height. We didn't realize that the vegetation flourishing on either side of the trail was so thick it was nearly impossible to maneuver our bodies into it.

"Damn, that stuff really stings!" She exclaimed before reaching for her field notebook to jot down data. I grinned and surveyed the sample she had found.

In actuality, we were in the middle of the Ecuadorian cloud forest. We had spent the last few days at the Santa Lucia Reserve, which was so remote that mules had to carry our overnight backpacks up to the top of the mountain where the ecolodge sits. Unfortunately, we did not get to ride the mules, but climbed up the grueling, steep trail ourselves which took close to three hours. However, our professor did stop us every 10 minutes to discuss a variety of plant families or to point out a bird. When I say bird, I mean any bird. Even every Tawny-bellied Hermit, which looks exactly as it sounds: brown and boring.

Many of us often used it as an excuse for a change of subject or a short break. In the middle of a long lecture on the copious plant families that exist in the cloud forest, someone would whisper frantically and point at a far-off tree, “Xavier, look!” Xavier, our program director and lead professor, immediately lost his thought, pulled out his binoculars, and searched the canopy. We’d spend 10 or so minutes peering out and watching a small bird flit between branches, before Xavier identified it and felt ready to move on.

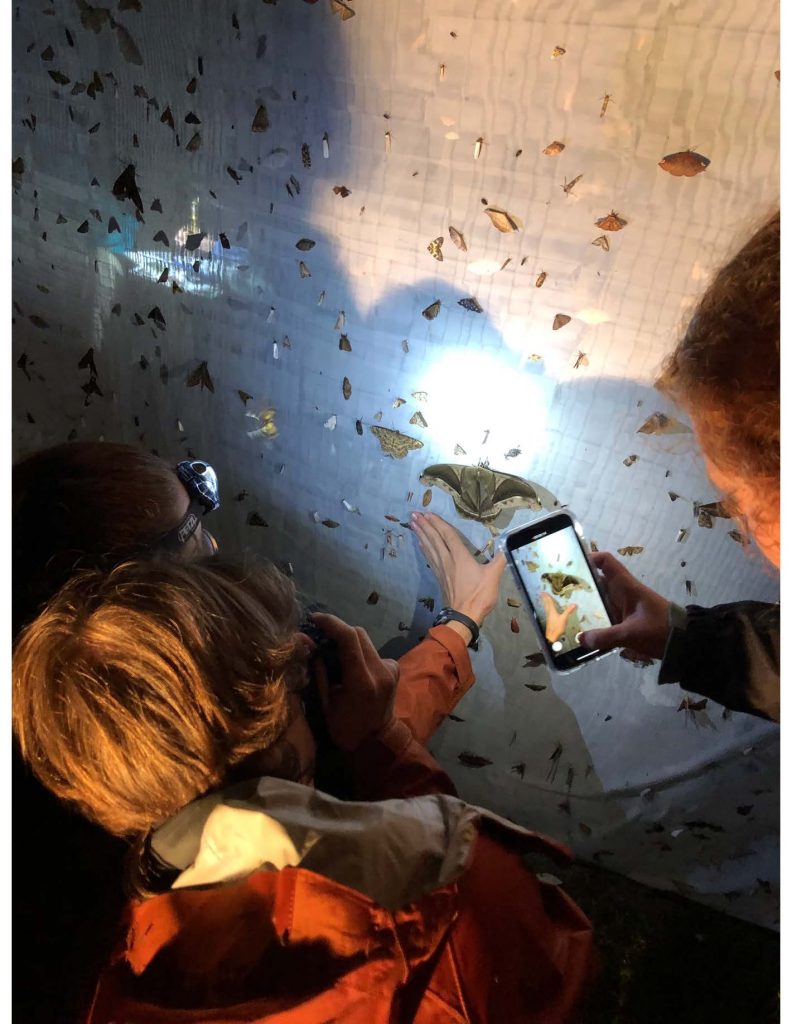

The moths that thrive in the Ecuadorian cloud forest are anything but average. Vibrant shades of orange and yellow, eye-like spots, some replicate leaves exactly, and some could be mistaken for birds because of their size.

We did find some beautiful birds, though. A toucanet perched outside the dining hall with an emerald green chest and long yellow beak. A Golden-Headed Quetzal calling softly from the canopy and ruffling his crimson and blue feathers. A wide variety of hummingbirds including the Long-Tailed Sylph, which, as you can imagine, has a tail twice or more the length of its body.

We also learned the methodology of mist netting, in which we set up three very thin nests along the ridge of the mountain to catch unassuming birds for two hours in the morning. We checked the nets every 30 minutes to minimize the time the birds spent stressed in captivity. Once caught, we measured their beak, wing, and tail length and identified the species. Many of the birds we studied were hummingbirds with a body weight less than 5 or 6 grams and bright, iridescent feathers.

Another study we conducted focused on the biodiversity and distribution of moths. If you're thinking about the types of moths that live in the States -- greyish-brown, fuzzy, and relatively small -- allow me to explain. The moths that thrive in the Ecuadorian cloud forest are anything but average. Vibrant shades of orange and yellow, eye-like spots, some replicate leaves exactly, and some could be mistaken for birds because of their size.

We hung a sheet over a clothesline and shined a light on it. We didn't have to wait long until it was covered in moths of all shapes and sizes. Each group was assigned a part of the sheet: back, front, left, or right, and measured the wingspans and identified the families of each moth in our quadrants. Within 10 minutes, we were covered in moths. They flew into our hair, on our faces, and all over our clothes. Tara, one of my research partners, accidentally smushed one in her notebook. Once we finished collecting data, we tried to no avail to rid ourselves of the moths before returning to the ecolodge.

It was one of the many crazy experiences of that week.

We did find some beautiful birds. A toucanet perched outside the dining hall with an emerald green chest and long yellow beak. A Golden-Headed Quetzal calling softly from the canopy and ruffling his crimson and blue feathers.

Speaking of crazy experiences, this brings me back to the mushrooms. Four of us chose to study the types of mushrooms and where they grow between the cloud forest and the Amazon for our Comparative Investigation Project. Our plan was to survey the area 2 meters on either side of the trail, noting the type of material the mushrooms grew on and at what height. We didn't realize that the vegetation flourishing on either side of the trail was so thick it was nearly impossible to maneuver our bodies into it.

I emphasize "nearly" impossible because we did it, but not necessarily pleasantly or easily. We crashed through the vines and leaves, often falling into seemingly invisible holes and making new friends with ants and spiders in the soil. But, we found beautiful and exotic mushrooms, often growing on decaying plant matter. Some looked like iridescent jelly and others like rust-colored shells. We emerged from each site, our clothes streaked chlorophyll green from the plants and spotted with mud, but giggling, and with smiles from ear to ear.

Xavier spoke to us about the intensity of the program and the heavy work load. He told us, "This is just a small taste of reality." He was referring to juggling many assignments at once and never being ahead of your to-do list, but I couldn't get past his word "reality." Exploring the cloud forest for five days and our upcoming trip to the Amazon was by no means a reality. More like, "Someone pinch me, I think I'm dreaming."

I feel more than grateful for the opportunity to explore and study these unbelievable, off-the-grid places that exist nowhere else in the world. And do I mention they are quickly fading away? From the deforestation for banana plantations to petroleum exploitation, the untouched beauty is being destroyed faster and faster. I know one day, very soon, it will all be wiped away by our greed to bleak piles of dirt and plumes of gas from the lush, vibrant biodiversity it is now. And my children and grandchildren will never see it, as I'm seeing it, with their own eyes.

So my gratitude is beyond anything I could begin to describe. As I gather my clothes, rain gear, and bug spray (tons and tons of bug spray) for the Amazon, I cannot believe I am experiencing this unimaginable, wild dream as a reality.